World

Unique Program Aids Children Displaced by Flooding in Alaska

An innovative educational initiative is supporting children displaced by severe flooding in Alaska. Following the devastation caused by Typhoon Halong last month, an estimated 700 homes were either destroyed or severely damaged in coastal villages along the Bering Sea. As a response to the crisis, many families, including that of Rayann Martin, were airlifted to Anchorage, where they are finding solace in a Yup’ik language immersion program.

During a recent class, Martin proudly raised ten fingers when asked her age, quickly engaging with the teacher’s inquiry about how to say “10” in Yup’ik. The students responded in unison with “Qula!” The immersion program is one of only two such initiatives in the state, focusing on the Yup’ik language and culture, which is vital for the identity of the Alaska Native community.

The flooding, which occurred on October 11, 2023, left one person dead and two others missing. As survivors adapt to their new circumstances, the immersion program offers a connection to their heritage. Martin expressed her gratitude, saying, “I’m learning more Yup’ik,” emphasizing that she uses the language more frequently with her family and peers than in her new urban environment.

With over 100 languages spoken among students in the Anchorage School District, Yup’ik ranks as the fifth most common, with approximately 10,000 speakers statewide. The district introduced its first language immersion program in 1989 and has since expanded to include several languages, including Spanish and Mandarin Chinese. Approximately nine years ago, a K-12 Yup’ik immersion program was established following parent requests, and the initial class is now composed of eighth-graders.

At the helm of the program is Darrell Berntsen, the principal at College Gate Elementary. Berntsen, an Alaska Native from Kodiak Island, understands the significance of preserving indigenous culture. His mother, who experienced the devastation of the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake, shared stories of resilience and community support after her village was flooded.

When families began arriving in Anchorage, Berntsen greeted them at a Red Cross shelter, encouraging them to enroll their children in the Yup’ik immersion program. He listened to their stories and offered a welcoming hand during a tumultuous transition. Many parents showed him photographs of traditional foods that were lost in the flood, underscoring the emotional toll the disaster took on their lives.

Currently, around 170 evacuated children have enrolled in the Anchorage School District, with 71 participating in the Yup’ik immersion program. Once the smallest immersion initiative within the district, it is now flourishing, according to Brandon Locke, the district’s world language director. At College Gate, students engage in Yup’ik instruction for half of the day, covering literacy, science, and social studies, while the remainder of their schedule focuses on English language arts and mathematics.

Among the newcomers is Ellyne Aliralria, a ten-year-old from Kipnuk. During the flooding, her family’s home was swept upriver, and she recalled the emotional pain of losing her sister’s grave. Aliralria appreciates the opportunity to learn more Yup’ik phrases, even though the dialect differs slightly from the one she is used to. “We’re homesick,” she said, reflecting the struggle many displaced families face.

Another student, Lilly Loewen, is not Yup’ik but enrolled in the program because her parents believed it would be beneficial. “It is just really amazing to get to talk to people in another language other than just what I speak mostly at home,” she shared.

To further support the new students, Berntsen plans activities that incorporate traditional Alaska Native practices, such as gym nights and Olympic-style events that mimic hunting and fishing techniques. One such activity, the seal hop, encourages participants to simulate the stealth required for hunting seals on ice.

The Yup’ik immersion program serves not only as an educational platform but also as a means of restoring cultural connections. It addresses the generational gap that has resulted in a loss of language among some families. Children now have the opportunity to converse with their great-grandparents, fostering intergenerational bonds that were previously weakened.

“I took this as a great opportunity for us to give back some of what the trauma had taken from our Indigenous people,” Berntsen stated, emphasizing the importance of cultural preservation amid adversity. As these children navigate their new lives, the immersion program offers a beacon of hope and a pathway to reestablish their cultural roots.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSecwepemc First Nation Seeks Aboriginal Title Over Kamloops Area

-

World4 months ago

World4 months agoScientists Unearth Ancient Antarctic Ice to Unlock Climate Secrets

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoTrump and McCormick to Announce $70 Billion Energy Investments

-

Lifestyle4 months ago

Lifestyle4 months agoTransLink Launches Food Truck Program to Boost Revenue in Vancouver

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoFour Astronauts Return to Earth After International Space Station Mission

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoApple Notes Enhances Functionality with Markdown Support in macOS 26

-

Top Stories1 month ago

Top Stories1 month agoUrgent Update: Fatal Crash on Highway 99 Claims Life of Pitt Meadows Man

-

Sports4 months ago

Sports4 months agoSearch Underway for Missing Hunter Amid Hokkaido Bear Emergency

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoUkrainian Tennis Star Elina Svitolina Faces Death Threats Online

-

Politics4 months ago

Politics4 months agoCarney Engages First Nations Leaders at Development Law Summit

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoFrosthaven Launches Early Access on July 31, 2025

-

Top Stories3 weeks ago

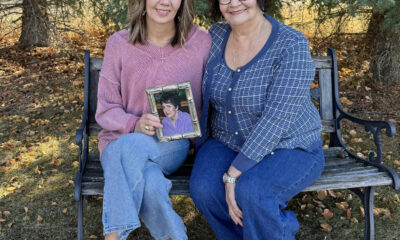

Top Stories3 weeks agoFamily Remembers Beverley Rowbotham 25 Years After Murder