When Thomas Hummel catches the scent of an unripe, green tomato, he is instantly transported back to his childhood home in Bavaria. Under the slanted ceilings of the bedroom he shared with his two older brothers, there were three beds, a simple table, and a cupboard. “My mother put those green tomatoes on the cupboard for them to ripen,” recalls Hummel, an olfaction researcher at the Carl Gustav Carus University Hospital in Germany. “They have this very specific smell.”

The aroma is grassy, green, pungent, rough, and bitter, he describes. Today, when he walks past a bin of tomatoes at the market, “it is always to some degree emotional,” he says, “like every smell is emotional.”

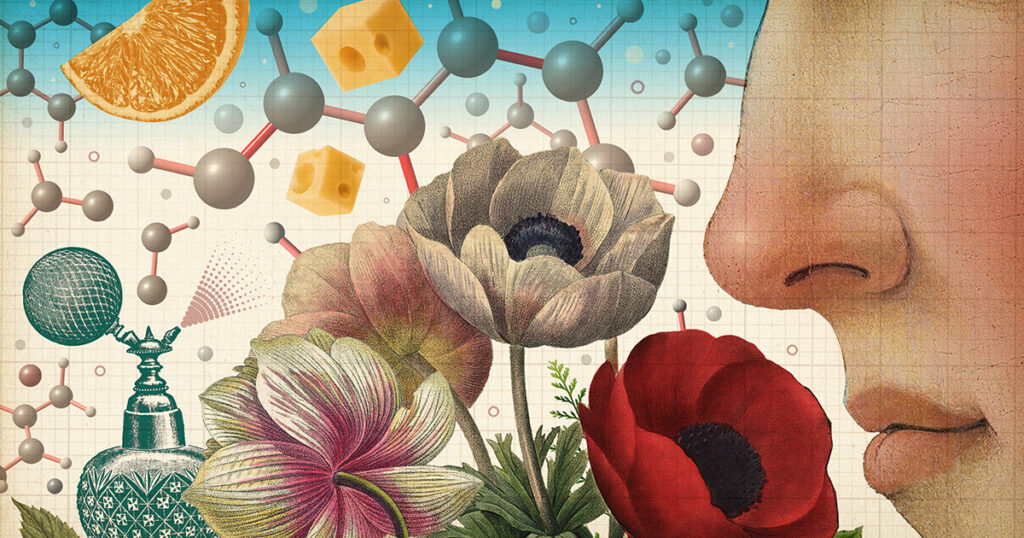

Smell is intricately linked with the emotion and memory centers of our brain. A lavender perfume might evoke memories of a close friend, while the scent of cheap vodka could bring back college days. The fragrance of a particular laundry detergent might even bring tears to one’s eyes, recalling grandparents.

The Ancient and Mysterious Sense of Smell

Smell is our most ancient sense, tracing back billions of years to the first chemical-sensing cells. However, scientists know relatively little about it compared to other senses like vision and hearing. This is partly because smell has not been deemed critical for survival; humans have long been considered “bad smellers.” Additionally, studying smell is inherently complex.

“It’s a highly dimensional sense,” says Valentina Parma, an olfactory researcher at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. “We don’t know exactly how chemicals translate to perception.” Yet, scientists are making strides in characterizing and quantifying what it means to smell by analyzing the process from odor molecules entering the nose to the neurons processing them in the brain.

Several new databases are attempting to establish a shared scientific language for scent perception, and recent studies are decoding how scent molecules trigger emotions and memories.

Challenging the “Non-Smeller” Myth

The notion that humans are poor smellers stems from a century-old misunderstanding. In the late 19th century, French neuroanatomist Paul Broca attempted to explain why humans possess free will, unlike other animals. He noted that humans have relatively small olfactory bulbs compared to their brain size, unlike animals like mice and horses.

Broca concluded that smell drives behavior in animals, which humans can choose to ignore, leading him to label humans as “anosmatique” or “non-smellers.” This idea was later misinterpreted by English anatomist Sir William Turner, who suggested humans are inherently bad at smelling.

“Through a series of telephone games, people just kept repeating the idea, ‘Oh, humans don’t need smell,’” explains Sarah Cormiea, a postdoctoral researcher studying olfaction at the University of Pennsylvania. Sigmund Freud’s musings further entrenched the belief that smell was a primitive sense.

However, research traces the mammalian sense of smell back 3 billion years to bacteria in ancient oceans, which detected chemical gradients to find food. This ability, called chemosensation, is the most rudimentary form of smell and has parallels in complex animals like mammals.

Decoding the Language of Smell

In the 1990s, biologists Linda Buck and Richard Axel discovered genes coding for odorant receptors in mammals. Studies revealed humans have around 400 types of olfactory receptors in the nose, with millions lining the nasal passages. Each receptor can recognize various odorants, molecules that evaporate into the air and enter the nasal passages.

When you smell a rose, over 800 different odorants bind to olfactory receptors, creating a pattern interpreted by the brain. There are 5.8 million molecules that could be potential odorants detectable by humans, although it’s unknown if we can smell them all, says Matthias Laska, a zoologist at Linköping University in Sweden.

“We tend to underestimate our sense of smell because we lack a vocabulary for it,” explains Antonie Bierling, an olfaction researcher at the Dresden University of Technology.

Describing smells is challenging, as our language often links them to their source. For instance, something might smell “grassy” or “like a wet dog.” This limitation has hindered the study of the human sense of smell.

Mapping the Complex World of Odors

Unlike light or sound, which can be easily mapped to specific wavelengths or frequencies, odors are complex and multidimensional. They often arrive as a bouquet of molecules that can smell different to each person based on context and past experiences.

“Real odors are complicated and multidimensional,” notes Cormiea. “People don’t have a good understanding of what features of an odor stimulus produce what perceptual experiences.”

Odorous molecules have various dimensions that define their smell, such as size, charge, and interactions with other molecules. Even chiral molecules, which are mirror images of each other, can smell completely different.

The ongoing research into the sense of smell is gradually unraveling its complexities, challenging the long-held assumption that it is our least important sense. As scientists continue to decode the language of smell, they are uncovering its profound impact on memory and emotion, offering new insights into this ancient and mysterious sense.