Politics

Courts Reject Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order Amid Legal Challenges

In a significant legal setback for President Donald Trump, multiple federal courts have blocked his executive order that seeks to end automatic citizenship for children born in the United States to parents who are in the country illegally or temporarily. Over the course of a month this summer, four federal courts issued rulings against the order, culminating in a unanimous decision from a three-judge panel of the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston on August 25, 2023.

The court’s ruling aligns with previous decisions from four other courts that have also blocked the implementation of the executive order nationwide. As the situation stands, the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to have the final say on the matter, with the Trump administration already requesting that the high court review the issue.

Legal analysts suggest that these consistent rejections highlight a fundamental conflict between the Trump administration’s stance and established Supreme Court precedents, as well as constitutional principles. The Supreme Court is not obligated to adhere to lower court rulings, but its previous decisions may pose challenges for the administration’s arguments.

14th Amendment and Birthright Citizenship

The concept of automatic citizenship at birth is rooted in the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1868. This amendment was designed to ensure that all individuals born or naturalized in the United States are recognized as citizens, particularly addressing the rights of formerly enslaved individuals. The citizenship clause specifies that all people born or naturalized in the U.S. and “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” are citizens.

Administration lawyers contend that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” indicates that citizenship is not automatically granted to children based solely on their birth in the U.S. They argue that this clause necessitates a primary allegiance to the United States, which they claim children of undocumented immigrants do not possess. Abigail Jackson, a spokesperson for the White House, asserted that the 1st Circuit misinterpreted the amendment.

Legal scholars argue that the administration’s interpretation fails to consider the historical context of the amendment. Experts suggest that lawmakers who debated the amendment intended it to encompass a broad definition of birthright citizenship, which would include the children of immigrants. The clause was primarily meant to exclude children of Native Americans on tribal lands and the offspring of foreign diplomats, who enjoyed immunity from U.S. jurisdiction.

Supreme Court Precedents and Recent Rulings

The Supreme Court has historically upheld the principle of birthright citizenship. In a landmark 1898 case, the court ruled that the son of Chinese immigrants, born in San Francisco, was a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment. Although the court has not directly addressed the citizenship rights of children born to undocumented immigrants, a footnote in a 1982 decision suggests no distinction should be made between these children and those of legal immigrants.

Earlier this year, the court’s conservative majority considered a challenge to the birthright citizenship order but opted not to determine its constitutionality. Instead, it issued a ruling limiting the authority of lower courts to issue nationwide injunctions, which was viewed as a victory for the administration. Nonetheless, the court did not dismiss the possibility of nationwide effects in class-action lawsuits or cases brought by states.

Court rulings have consistently blocked Trump’s executive order, beginning with a federal judge in New Hampshire. Recently, judges have certified a class of children born in the U.S. after the order’s effective date, who would be denied citizenship based on it. Courts have also agreed with states that a fragmented application of the order would impose financial burdens on them, given the frequent movement of individuals between states.

The 1st Circuit expressed clarity in its decision, with Chief Judge David Barron stating, “The length of our analysis should not be mistaken for a sign that the fundamental question…is a difficult one.” He emphasized the long-standing nature of the principle of birthright citizenship, noting that it has been over a century since an effort has been made to deny Americans their birthright.

In response to the court’s ruling, Jackson expressed the administration’s anticipation of vindication from the Supreme Court. To enact the order, officials would need to verify parental citizenship or immigration status before issuing Social Security numbers, and passport applications would require similar proof, according to recent guidance.

As the legal battle continues, the outcome at the Supreme Court could have far-reaching implications for immigration policy and birthright citizenship in the United States.

-

World3 months ago

World3 months agoScientists Unearth Ancient Antarctic Ice to Unlock Climate Secrets

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoTrump and McCormick to Announce $70 Billion Energy Investments

-

Science3 months ago

Science3 months agoFour Astronauts Return to Earth After International Space Station Mission

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoTransLink Launches Food Truck Program to Boost Revenue in Vancouver

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoApple Notes Enhances Functionality with Markdown Support in macOS 26

-

Top Stories1 week ago

Top Stories1 week agoUrgent Update: Fatal Crash on Highway 99 Claims Life of Pitt Meadows Man

-

Sports3 months ago

Sports3 months agoSearch Underway for Missing Hunter Amid Hokkaido Bear Emergency

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoUkrainian Tennis Star Elina Svitolina Faces Death Threats Online

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoFrosthaven Launches Early Access on July 31, 2025

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoCarney Engages First Nations Leaders at Development Law Summit

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoCalgary Theatre Troupe Revives Magic at Winnipeg Fringe Festival

-

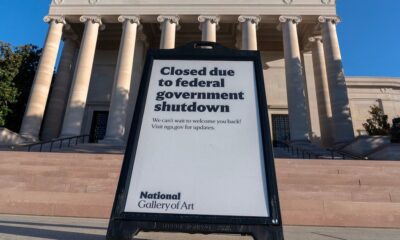

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoShutdown Reflects Democratic Struggles Amid Economic Concerns