Science

Global Agreement Protects Sharks and Rays from Extinction

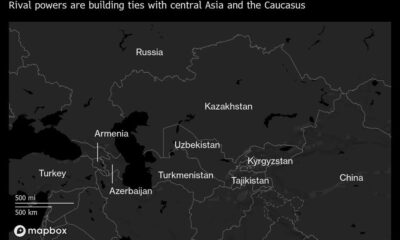

Global governments have taken a significant step toward protecting endangered marine life, implementing sweeping international trade bans and restrictions on over 70 species of sharks and rays. The decision emerged from the 20th Conference of the Parties (COP20) of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) held in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, marking a pivotal moment in marine conservation efforts.

The newly adopted measures include protections for notable species such as the oceanic whitetip shark, whale shark, and manta ray. These species play crucial roles as apex predators, maintaining the health of marine ecosystems. According to Luke Warwick, director of shark and ray conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the global market for these species has reached nearly $1 billion annually, driven largely by the demand for shark meat, fins, and other products.

More than a third of shark and ray species now face extinction threats, with populations of pelagic sharks declining by over 70 percent in the last 50 years. Reef sharks have virtually disappeared from one in five coral reefs worldwide. Warwick emphasized the urgency of the situation, stating, “We’re in the middle of an extinction crisis for these species, and it’s kind of a silent crisis.”

The new protections, which received nearly unanimous support from CITES’ 185 member countries and the European Union, prohibit international trade for certain species and impose strict regulations on others. Notably, the oceanic whitetip, whale sharks, manta rays, and devil rays are now listed under CITES’ Appendix I, signaling their high risk of extinction due to trade.

Diego Cardeñosa, an assistant professor at Florida International University, described these protections as a critical step towards recovery for these species. He noted, “If you find an oceanic whitetip fin being traded, 90 days from here onwards, that’s an illegal product.”

For decades, sharks and rays have been treated like other fast-reproducing fish, despite their slow maturity and low reproductive rates. For instance, manta rays may give birth to only seven pups in their lifetime. This stark difference has contributed to their decline, as they have been caught and killed in overwhelming numbers.

Manta rays are particularly sought after for their gill plates, often used in traditional Asian medicine, although scientific evidence supporting these claims is lacking. Shark fins are a delicacy in luxury cuisine, especially in shark fin soup, while shark meat is increasingly consumed as a low-cost protein source and used in pet food. The liver of deep-water species is harvested for its oil, a key ingredient in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, including some COVID-19 vaccines.

The unchecked trade in these species has led to population declines of over 80 percent in certain regions. Gabriel Vianna, a shark researcher from the Charles Darwin Foundation, highlighted the role of the cosmetic industry in driving the demand for shark products. He advocated for the use of synthetic alternatives instead of exploiting these vulnerable species.

The new CITES decisions represent a turning point in marine conservation. Historically, the treaty has focused on iconic land species, such as elephants and rhinos. Only in the last decade has it begun to recognize the urgent need to protect sharks and rays. Warwick noted that the unanimous adoption of protections for these species at COP20 is unprecedented.

The European Union, a major supplier of shark meat to Southeast Asia, has been implicated in the global trade, accounting for over 20 percent of it, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Under the new regulations, species such as gulper sharks and smoothhound sharks will be listed in CITES’ Appendix II, requiring member countries to ensure that their international trade is sustainable.

For many advocates, the new protections bring mixed feelings. Vianna expressed that while there is relief at the new listings, there is also a deep concern for the future of these species. “We shouldn’t be happy about this species being listed. We should actually be really worried that there’s such a problem with them,” he said.

Effective implementation of these new protections will be vital. Research by Cardeñosa and Warwick revealed significant discrepancies between reported shark fin trade and actual trade levels, with genetic analyses indicating that over 90 percent of oceanic whitetip shark fins in the market were illegally traded.

With the oceanic whitetip now classified under Appendix I, Cardeñosa is hopeful that enforcement gaps can be closed. He stated, “The new listings will not eliminate illegal trade overnight, but they will significantly strengthen the ability of countries to inspect, detect, and prosecute illegal shipments.”

Investment in identification tools, capacity building, and ongoing monitoring will be essential for translating these protections into tangible results. As nations unite to combat the decline of sharks and rays, the world watches closely, hopeful for a future where these majestic creatures thrive once more.

-

Politics1 month ago

Politics1 month agoSecwepemc First Nation Seeks Aboriginal Title Over Kamloops Area

-

World5 months ago

World5 months agoScientists Unearth Ancient Antarctic Ice to Unlock Climate Secrets

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoTrump and McCormick to Announce $70 Billion Energy Investments

-

Lifestyle5 months ago

Lifestyle5 months agoTransLink Launches Food Truck Program to Boost Revenue in Vancouver

-

Science5 months ago

Science5 months agoFour Astronauts Return to Earth After International Space Station Mission

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoManitoba’s Burger Champion Shines Again Amid Dining Innovations

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoApple Notes Enhances Functionality with Markdown Support in macOS 26

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoUrgent Update: Fatal Crash on Highway 99 Claims Life of Pitt Meadows Man

-

Top Stories2 weeks ago

Top Stories2 weeks agoHomemade Houseboat ‘Neverlanding’ Captivates Lake Huron Voyagers

-

Politics4 months ago

Politics4 months agoUkrainian Tennis Star Elina Svitolina Faces Death Threats Online

-

Sports5 months ago

Sports5 months agoSearch Underway for Missing Hunter Amid Hokkaido Bear Emergency

-

Politics5 months ago

Politics5 months agoCarney Engages First Nations Leaders at Development Law Summit