Science

Global Governments Enact Landmark Protections for Sharks and Rays

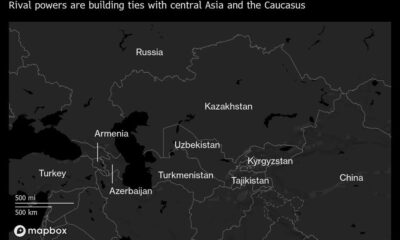

Governments around the world have taken a historic step to protect sharks and rays from extinction by agreeing to impose international trade bans and restrictions. This decision affects over 70 species, including the oceanic whitetip shark, whale shark, and manta ray, under the auspices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The new safeguards were established during the 20th Conference of the Parties (COP20) held in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, marking a significant commitment to address the dwindling populations of these species.

Sharks and rays play critical roles in maintaining healthy marine ecosystems as apex predators. According to Luke Warwick, director of shark and ray conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the global market for these species is nearly worth $1 billion annually. The recent measures aim to curb the demand for shark meat, fins, and other products derived from these animals.

“These new protections are a powerful step toward ensuring these species have a real chance at recovery,” noted Diego Cardeñosa, an assistant professor at Florida International University and lead scientist at the school’s Predator Ecology and Conservation Lab. He emphasized that more than a third of shark and ray species are currently threatened with extinction, highlighting a crisis that has been exacerbated by overfishing.

Population declines among pelagic sharks—those that inhabit the open ocean—have exceeded 70 percent over the last 50 years. Reef sharks have nearly disappeared from one in five coral reefs globally. “We’re in the middle of an extinction crisis,” Warwick stated. Unlike commercially regulated species such as tuna, sharks have historically lacked stringent trade controls, treated as if they were fast-reproducing fish. In reality, sharks and rays mature slowly and produce far fewer offspring, complicating their recovery.

The manta ray, for example, may give birth to only seven pups in its lifetime. Their gill plates are sought after for traditional medicines in Asia, despite the absence of scientific support for such claims. Shark fins, particularly prized in luxury Chinese cuisine, are often featured in dishes like shark fin soup, while shark meat is increasingly marketed as an affordable protein source. Additionally, the oil from deep-water species like gulper sharks is harvested for use in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, including COVID-19 vaccines.

Unregulated trade has resulted in population declines of over 80 percent in certain regions. “The cosmetic industry is driving the trade of sharks,” remarked Gabriel Vianna, a researcher from the Charles Darwin Foundation. Despite increasing awareness and concern, there were previously no international controls on the trade of these species until the recent CITES decisions.

The new protections represent a turning point in marine conservation. For much of its 50-year history, CITES focused primarily on protecting land species such as elephants and rhinos, and more recently, marine species like sea turtles. It wasn’t until the last decade that sharks and rays began receiving the urgent attention they require. This year, the unprecedented unanimous support from CITES’ 185 member countries and the European Union led to the adoption of all proposed protections for these species.

The European Union is a significant supplier of shark meat to Southeast and East Asian markets, contributing over 20 percent to global shark meat trade, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Under the new CITES listings, gulper sharks and smoothhound sharks are classified under Appendix II, which mandates strict regulations for international trade. Certain species, including wedgefish and giant guitarfish, are now temporarily protected from trade, while oceanic whitetips, whale sharks, manta rays, and devil rays are granted Appendix I status, marking them as facing real extinction risk.

Under these new regulations, the international trade of oceanic whitetip fins will be illegal within 90 days from the adoption of the measures. While many advocates celebrate the new listings, they also express concern. “We are very happy but we are very sad at the same time,” said Vianna, emphasizing that the need for these protections underscores a critical problem.

The effective implementation of these protections will be essential for the survival of many species. Research by Cardeñosa and Warwick, published in November 2023, found that fins from several shark and ray species were frequently detected in Hong Kong, the world’s largest shark fin market, during the period from 2015 to 2021. The study revealed significant discrepancies between legal trade records and the actual number of species being traded, suggesting that over 90 percent of the trade in certain species is illegal.

“The new listings will not eliminate illegal trade overnight,” Cardeñosa acknowledged. “However, they will significantly strengthen the ability of countries to inspect, detect, and prosecute illegal shipments.” To ensure these protections translate into tangible results, parties must invest in identification tools, capacity building, and routine monitoring.

As the international community moves forward with these landmark protections, the focus will remain on closing loopholes and enforcing regulations to safeguard the future of sharks and rays.

-

Politics1 month ago

Politics1 month agoSecwepemc First Nation Seeks Aboriginal Title Over Kamloops Area

-

World5 months ago

World5 months agoScientists Unearth Ancient Antarctic Ice to Unlock Climate Secrets

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoTrump and McCormick to Announce $70 Billion Energy Investments

-

Lifestyle5 months ago

Lifestyle5 months agoTransLink Launches Food Truck Program to Boost Revenue in Vancouver

-

Science5 months ago

Science5 months agoFour Astronauts Return to Earth After International Space Station Mission

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoManitoba’s Burger Champion Shines Again Amid Dining Innovations

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoApple Notes Enhances Functionality with Markdown Support in macOS 26

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoUrgent Update: Fatal Crash on Highway 99 Claims Life of Pitt Meadows Man

-

Top Stories2 weeks ago

Top Stories2 weeks agoHomemade Houseboat ‘Neverlanding’ Captivates Lake Huron Voyagers

-

Politics4 months ago

Politics4 months agoUkrainian Tennis Star Elina Svitolina Faces Death Threats Online

-

Sports5 months ago

Sports5 months agoSearch Underway for Missing Hunter Amid Hokkaido Bear Emergency

-

Politics5 months ago

Politics5 months agoCarney Engages First Nations Leaders at Development Law Summit